“We interrupt this program for a special news bulletin.”

On Feb. 3, 1959, these were the words more than likely heard from the television in a young woman’s Greenwich Village apartment. She was a little over a month pregnant. Her husband had been gone for roughly three weeks, but he would be back as soon as his tour was finished.

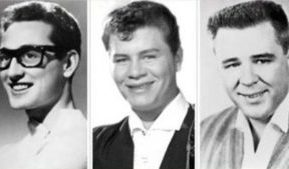

“Three young singers who soared to the heights of show business on the current Rock ‘n’ Roll craze were killed today in the crash of a light plane in an Iowa snow flurry. The singers were identified as Ritchie Valens, 17, Buddy Holly, 22, and J.P. Richardson, known professionally as ‘The Big Bopper.’”

It would be in this moment that María Elena Holly would learn of her husband’s death. Not from her family, or the police, but from a newscast.

Buddy Holly, a rising American rock and roll singer, had been killed in a plane crash during the early weeks of his tour across the Midwest. The day after his death, Feb. 4, his wife of only five months would suffer a miscarriage caused by the psychological toll of learning of her husband’s death from the television.

At the same time, a little under 2,000 miles away in her home in Texas, Buddy’s mother Ella would turn on her radio at the persistence of a neighbor, only to hear a similar broadcast to that of her son’s wife. It would be in that same living room her son had grown up in that she would collapse from the news of his death spilling from the speakers on her radio.

“This story in from Clear Lake, Iowa. Three of the nation’s top rock and roll singing stars, Ritchie Valens, J. P. ‘The Big Bopper’ Richardson and Buddy Holly died today with their pilot in the crash of a charted plane.”

Another 2,000 miles from there, Robert ‘Bob’ Morales was working on his 1950 Oldsmobile when a neighbor approached to tell him the story he’d heard on the radio, asking if his mother was at his childhood home. At nearly the same time, Connie and Irma Valens would be approached by a girl on the walk home from school, echoing a similar statement about the radio.

It would be when the three siblings reached their mother’s house that they would learn what she had: Their 17-year-old brother, American rock and roll singer Ritchie Valens, had been killed in that same plane crash alongside Buddy Holly only eight months after the peak of his sudden fame, and each of them had found out because of the news reports.

This incident, now immortalized as “the day the music died” in Don McLean’s “American Pie,” was a major tragedy, then a major controversy for journalism.

Journalists across the nation are expected to follow certain sets of rules, regulations and ethical standards. While these standards often vary between individual publications and the common ideals of publishing areas, the Society of Professional Journalists have a code of conduct that largely outlines the ethics expected to be used by all members of the media.

According to the SPJ, ethical journalism should be accurate and fair to all parties. There are four principles the SPJ use to classify ethical journalism: “Seek truth and report it,” “minimize harm,” “act independently” and “be accountable and transparent.

According to reporter Claire Suddath in her 2009 TIME article “The Day the Music Died,” in the months following the 1959 crash, multiple media outlets across the United States adopted ethical policies for their individual publications against publishing names of recently deceased victims until they were informed the family had been notified.

Clause 7.2.9 of the Impress Standards Code to privacy outlines the general ethics journalists are expected to uphold when reporting on a death, specifically how the journalist approaches the story.

According to this section of the clause, journalists should take great care when approaching family, friends or loved ones of a deceased person “to avoid [anything] that may result in the harassment of a person suffering from grief or shock.” Along with this, journalists are expected to avoid publishing any details that may increase the personal suffering of a deceased person’s loved ones.

“Ideally, journalists should not publish images of identifiable individuals related to a traumatic event or death unless the consent of the individual concerned, or their family, has been obtained,” the clause also reads.

Along with this code of conduct of the guidelines provided by SPJ, individual publications and reporters are also expected to generate and uphold their own ethical standards.

“The greater good always comes first, because that’s where ethics come from,” Sherine Mansour, Sheridan College’s New Media Coordinator, said in an interview with Jon Kuiperij in 2021. “Responsible journalism is about taking care of the weak — those without a voice and those who have no recourse or protection. If you’re coming from that place first and foremost, then the ethics decide themselves.”

As journalism progresses into the digital age, ethics are more important than ever.

According to the PEW Research Center, only half of Americans in 2020 trusted the information and reporting of US news media. The emergence of “fake news,” the publication of distressing images and reports, biased journalism and concerns that journalists do not act in the best interest of the public are the driving forces behind this distrust.

According to the Poynter Institute, when compared to surveys given in 46 countries, America ranked last when it came to citizen trust in the media, with only 29 percent of those surveyed saying they felt as though the information they received was truthful.

“Fake news affects the way people interpret reality and can influence everything from election results to climate change initiatives,” an article published by St. Bonaventure University reads. “Journalists can help the public navigate the complex and ever-changing landscape of news, with truth, and ethical reporting.”

While significant improvements have been made to journalism ethics since the coverage of “the day the music died,” they are still dependent on the beliefs of the public, publication and individual reporter.

The shared idea that journalism ethics are important, however, is commonly accepted and believed by the majority of journalists.

“…Public enlightenment is the forerunner of justice and the foundation of democracy,” the preamble to the SPJ Code of Ethics reads. “Ethical journalism strives to ensure the free exchange of information that is accurate, fair and thorough. An ethical journalist acts with integrity.”

Editor’s Note: The quotes at the beginning of this story were taken from audio recordings of reports from Feb. 3, 1959. The recordings, both found on YouTube, were from a news station with the call sign Action News Central and a New Orleans radio station, respectively.

Written by Bailey Storey, Co-Editor in Chief. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia.

The Spectator The independent student newspaper of Valdosta State University

The Spectator The independent student newspaper of Valdosta State University